This is an examination of the work of Demian DinéYazhi’ by curator, arts manager and educator Anna Harsanyi. In the work of Demian DinéYazhi’, language and performance are creative tactics for puncturing the United States’ long history of erasure and destruction of Indigenous communities. Using the performative and confrontational power of text, DinéYazhi’ engages with the continued resistance work of marginalized communities. The artist’s provocations form moments to call today’s socio-politics back into their contexts of settler-colonial systemic violence. America in 2020 was consumed with many layers of devastation and chaos, including the Presidential election. Social media echoed the frustrations of many over a ballot of, yet again, cis white men. Circulating amongst social networks in the months before the election was Zoe Leonard’s 1992 poem I want a president, which begins: “I want a dyke for president. I want a person with aids for president and I want a fag for vice president and I want someone with no health insurance and I want someone who grew up in a place where the earth is so saturated with toxic waste that they didn’t have a choice about getting leukemia.” Leonard’s poem goes on to name those harmed by mechanisms of political inequality, demanding a President who represents her LGBTQIA+ community, and who has experienced struggle, and whose body has faced injustice. Though Leonard’s poem appeals to inclusivity and “we see you” empowerment, the feminist and queer artistic movements she was a part of also excluded Indigenous, Black, Brown, womxn of color, and non-binary individuals. Her statement, often looked to as an iconoclastic work of contemporary art activism, is furtively checked for its omissions by DinéYazhi’, who extends an alternative, more urgent, set of demands in We don’t want a president. (2018). These begin with:

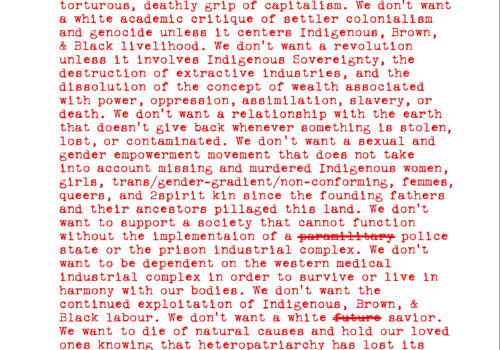

“We don’t want a president. We don’t want tribal presidents. We don’t want a vice president or a congress or supreme court that does not seek consent or guidance from over 562 Indigenous tribes in this colonized country. We don’t want a nation state or a man-made border that severs ancestral traditions of trade and migration, or imposes on the sustainability of flora and fauna.”

The text continues towards a detailed and powerful reframing of what it in fact means to desire revolution or representation within the format of American government: the Executive Office and all of its administrative bodies are ultimately tools that perpetuate illegitimate occupations of Indigenous land and culture, and continued violence against its people. There can be no perceived “change,” “freedom,” “justice,” or any other shift when these outcomes are linked to the United States’ institutional practices. Through these assertions, DinéYazhi’ breaks open the common framings of public discourse, even amidst the purported progressivism of so-called “radical” social and cultural frameworks. In another instance, a recent performance titled SHATTER///, a collaboration with artist and composer Kevin Holden, was live-streamed at Portland Institute for Contemporary Art in September 2020. In a dimly lit room cloaked in a red glow, the artist recounts personal experiences as well as histories of Indigenous oppression. Holden’s guitar and pedals emit raw intensity, that at times envelop the vocals in cacophony. At a moment of crescendo in both the oration and the musical score, a destruction occurs. Behind the performers is a collection of objects that represent racist Indigenous stereotypes – a VHS of Disney’s animated film Pocahontas, a porcelain “Indian” tchotchke, and more; these were gathered in preparation for the performance at local thrift stores and antique stores/malls in the area. Thrown to the ground, stomped on, broken apart, their shattering is at once physical and metaphorical. This is an act of confrontation of the oppressive systems that created such racist objects, alongside the communities who consume and distribute both their material objecthood and the harmful meanings they encapsulate. Their obliteration, realized parallel to a wall of piercing sound, is a symbolic rupturing of the very social and political fabric that upholds these value systems, and their justification as harmless relics of “another time.” Though SHATTER/// has been performed in several venues in previous years, witnessing such breakage is especially cathartic and fiery in the present day. As conversations unfold about the future of the United States’ racist monuments and cultural heritage, and the history of atrocities they represent, smashing the material culture of this history and diminishing it to residue signals a reclamation of power necessary for confronting all efforts towards decolonization. Part of what makes the work of DinéYazhi’ so poignant is its intentional development outside of the boundaries set up by institutional structures. Their work does not “need” an institution or an exhibition in order to take place, in order to thrive and take powerful hold over an audience. Viewership is a relationship that the artist cultivates through a deep engagement with their practice as part of existing legacies of collective resistance. The magnitude of DinéYazhi’’s work becomes apparent through a delicate employment of the poetics of radical criticality. The work is often described by the artist as a gesture or an offering, an affective creative process rooted in deep intention and critical purpose. Such careful consideration allows for an experience of work that entwines form and context. Another one of DinéYazhi’’s projects, AN INFECTED SUNSET, serves as one such offering to the resistance work of marginalized communities, work that has been ongoing for centuries. A self-published long form text which is sometimes accompanied by a performative reading, it was conceived of in 2016, when large-scale violent injustices occurred in quick succession: the PULSE shooting in Orlando; the uprising at Standing Rock; the police suppressions of Black Lives Matter protests; the contentious election of Donald Trump. Though the artist could not join these movements in person, AN INFECTED SUNSET, which they wrote between 2016-2018, served as a means to contribute their energy towards these actions. It was delayed and shifted in style and content due to Trump’s election. The text is personal and reflective, critical and observational. It speaks of interior and exterior, but also historical and contemporary, lived experiences. The second half of the book, LIBERATED POEM, is unbound and the pages are not numbered–free from book form. When performing a reading, the artist leaves the pages to fall to the ground as they read from it, to be taken away by audience members or linger where they fall. But these words and messages are not discarded. They remain, as the artist recently stated, “a ceremonial offering to community…I think of poetry and performance and writing as gestures of that continued role and dedication that the artist has to communities. I may not always be able to show up or be there physically, but my work will…create space, opportunities and awareness about these atrocities that are happening and that we are actively resisting.” Image caption: Demian DinéYazhi’ and Radical Indigenous Survivance & Empowerment (R.I.S.E), We don’t want a president., 2018. Image alt text: Red typewritten text on a white background that reads: “We don’t want a president. We don’t want tribal presidents. We don’t want a vice president or a congress or supreme court that does not seek consent or guidance from over 562 Indigenous tribes in this colonized country. We don’t want a nation state or a man-made border that severs ancestral traditions of trade and migration, or imposes on the sustainability of flora and fauna. We don’t want corporations or an economic value system based on European dominion. We don’t want to be consumed, commodified, or held prisoner under the tortuous, deathly grip of capitalism. We don’t want a white academic critique of settler colonialism and genocide unless it centers Indigenous, Brown, & Black livelihood. We don’t want a revolution unless it involves Indigenous Sovereignty, the destruction of extractive industries, and the dissolution of the concept of wealth associated with power, oppression, assimilation, slavery, or death. We don’t want a relationship with the earth that doesn’t give back whenever something is stolen, lost, or contaminated. We don’t want a sexual and gender empowerment movement that does not take into account missing and murdered Indigenous women, girls, trans/gender-gradient/non-conforming, femmes, queers, and 2spirit kin since the founding father and their ancestors pillaged this land. We don’t want to support a society that cannot function without the implementation of a paramilitary police state or the prison industrial complex. We don’t want to be dependent on the western medical industrial complex in order to survive or live in harmony with our bodies. We don’t want a white future savior. We want to die of natural causes and hold our loved ones knowing that heteropatriarchy has lost its own war against itself. We want to create on our own terms, in bodies of our own choosing. We want to restore our relationship with the cosmos/earth and move beyond the concept of western “truth”. We want to be fearless. We want decolonization. We want to exist never having to comprehend the need to defend ourselves. To worship only the earth. Part of the exhibition A NATION IS A MASSACRE. Demian DinéYazhi’ R.I.S.E. : Radical Indigenous Survivance & Empowerment.” ]]>