Zai Nomura: My answer is “yes, it’s possible.” Sara Wallgren: Do you think that you can become inspired through an online platform indefinitely, or is it limited to this exceptional period of time? ZN: I think the internet has the potential to inspire me all the time. Since our last conversation, when we spoke about how hard it is to work in isolation, I began to research and reconsider how we use the internet (Zoom, Instagram, Google Hangout, etc.) to create new artwork. I realized that the internet is such a young material for art, and that not many artists “use” it in a very effective way. SW: Yes, I guess you’re right. I also think that there is an interesting connection between what our inspiration is and how that is manifested in our work. So, since much of our interactive “art-lives” have moved online these days, it makes sense that this becomes our new platform for producing work. However, I can’t help missing that which is unplanned, such as an “unplanned studio visit” from a friend who visits the studio for a coffee and happens to have a comment about a work in progress. ZN: Right. SW: I don’t see how I can substitute this situation via digital media. ZN: That is very interesting. “Unplanned” is also a weaknesses of AI. SW: Yes. Even the unplanned in AI is planned. ZN: How about if a human chance-encounter could happen through the internet-medium? The ISCP Google Hangout conversations are planned. SW: Sure! Now I am thinking about what is provided via these new forms of communication. I guess that by sitting in front of the computer, we can control the direction of the person’s gaze who we are speaking with, as long as there is only one camera. But if there were multiple cameras as part of every conversation, controlled by the person outside of the room, then control would be lost. (Resembling having someone in the room looking around.) A limited spontaneity? And a bit creepy perhaps. ZN: Yes, it is. Even though the system looks like it’s created for “multiple communications,” only one person talks to another person, and other people can’t get into the conversation in a good way. However, how about if we could do something to the single camera directly, not in terms of hacking or digitally but more like attaching a paper or picture? Then, we could change the actual room that is seen online, like room decoration. SW: Ah this is interesting. Not using the online platform for a digital medium but an analog medium? ZN: Yes. Then people in Zoom will be surprised and feel very odd. SW: Haha, yes. ZN: That can be one idea about how to criticize the internet as an art material. If we take a step back from Zoom in order to reconsider or reconstruct it, then we could kind of get over the internet. That is why I said that the internet is still a young material. SW: This makes me think about how these new uses of the internet might not only become a development of internet-based art, but also performance! In Zoom or Google Hangout, since it’s a bit more intimate—and at the same time it is not intimate—everyone has the same distance from the “artwork.” In this scenario, isn’t everyone on the call a participant in a time-based artwork? ZN: That is a very cool perspective, I agree. I think a time-based process is one way to deconstruct the internet, another way can be materialization. SW: I’m looking forward to seeing new art emerging in the next couple of months and years. It will be interesting to see how artists respond to these new conditions, the internet and inspiration. ZN: Yes, this is kind of the same as the movie “Planet of the Apes”. SW: Haha, yes! ZN: This is a new tool for us.]]>

Residents Zai Nomura and Sara Wallgren in Conversation

June 18, 2020

by Zai Nomura and Sara Wallgren

New Red Order and the Complexity of Process

December 23, 2020

by Anna Harsanyi

This is an analysis of New Red Order’s “kaleidoscopic” art practice by curator, arts manager and educator Anna Harsanyi. A two-channel video by New Red Order (NRO), Culture Capture: Crimes Against Reality (2020), begins with the dissolution of James Earle Fraser’s 1918 bronze sculpture, End of the Trail. Dejected and weary, an “Indian” (as Fraser referred to him) slumps over his horse–a portrait of suffering meant to signify the agony inflicted upon Indigenous people by United States occupation. Fraser created work during an era of arrogant, violent, and illegitimate Western expansion. Today, the sculpture reflects the problematic state of the American monument. Who does a monument serve to commemorate? What atrocities are effaced in the act of memorialization? As monuments erode and the brutal contexts allowing for their existence are being discredited, public conversations increasingly center polarities such as truth vs lies, fake vs real. On one end of the spectrum, monuments are valued for their representations of a vague heritage, and at the other end they are visualizations of hateful exertions of authority. Both sides agree, however, that they are symbols of power. And so when such monuments deteriorate, whose power dissolves along with them? What truths emerge from this process of dissolution? NRO’s video calls to mind questions like these. The “crimes against reality” we are to about to witness are tied to the ones embedded in monuments, tributes to the genocidal origin story of America as an enduring settler colonial nation-state. In the beginning of the video, the sculpture, situated on a sunny islet, crumbles into pieces. A message to the viewer then fills the screen: “To erect a statue is to enact revenge on reality. And reality in turn exacts its due…” We then see archival material, the sculpture’s source images, and work-in-progress, flash in rapid succession. These are the visual fragments of statue erection, of reality in the process of distortion. The imagery also depicts the creation of another sculpture by Fraser: the controversial monument to Theodore Roosevelt installed outside of the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (but soon to be removed). Series of images continue to fly by, they are photogrammetry captures of the statue in full, pictures taken at all angles to allow for 3D imaging. Unlike Fraser’s End of the Trail equestrian, Roosevelt’s figure is one of strength and valiance, a military man astride a large horse. Walking alongside him at each of his feet are representations of Fraser’s imaginations of primitive peoples: an Indigenous and an African person. They buttress Roosevelt, the enduring figure of an era of conquest excused away by the pretext of manifest destiny. In the juxtaposition of these sculptures, we see two perspectives on Indigenous oppression: when depicted at the boot tip of a White colonizer, the subjugated is upright, moving forward. But portrayed on his own, he is defeated, stagnant. As the video progresses, both equestrians transform into 3D fleshy mutations of themselves, the closeups of their bronze textures morphing into a gooey substance filling the frame. The living beings depicted in the sculptures are being turned inside out. They are being transferred from their status as hardened symbols of a version of America to embodiments of the real-life horrors inflicted on oppressed bodies in this country. The viewer is presented with variations on a crime–not the depiction of an illicit act taking place, but a re-capture of cultural iconography suspended in the sinister reality that allowed for its creation. Indeed, one scene in the video shows Roosevelt’s statue vandalized with “NRO” splattered in red paint across the façade of the museum behind it. This is an act not of destruction, not of tearing down norms or ideals, but a capture that must take place–can only take place–against the brutal backdrop of reality. New Red Order is a public secret society whose work engages with the complexity of the discourse and experiences of Indigeneity. The group, whose core members are Jackson Polys, Adam Khalil and Zack Khalil, is a network of collaborators (referred to as informants and accomplices) who challenge settler-colonial impulses and the omnipresent barriers that threaten Indigenous agency. Their projects are multi-valent and difficult to place into a singular context. Their official configuration is intentionally obscure, allowing for a focus on the work itself as opposed to who is making it. Experiencing NRO’s work is to join a series of situations that poetically engage with the discomfort that arises in an honest interrogation of Indigeneity. They do not shy away from the politics of viewership or the complexities threaded throughout their subject matter. As Adam Khalil stated recently, the group explores “how to create new language that isn’t focused on ‘re-‘ or ‘de-‘…so that it is not focused on settler colonialism,” but devises a strategy to shift beyond binary frameworks of opposition. Just as the equestrians’ physical and material inversion in Culture Capture: Crimes Against Reality, NRO’s work is a turning inside out of how we critically understand Indigeneity and settler-colonialism. Through videos, installation, and performative actions, they enlist viewers towards this tough but urgent reckoning. NRO’s work calls into question how we frame who is and is not a settler, inciting audiences to move between the nuances of complicity of the individual and the more direct culpability of our systems of power. Eschewing the messaging of activist forms, NRO does not seek to define who should or should not join them. They call in many voices to alter critically the grand spiraling that is settler-colonialism, to build beyond it in order to overthrow it. Using the source material and visual language from actual appropriations of Indigeneity, NRO’s work constantly shifts back and forth between existing in the conceptual realm, and having practical applications to real life. Occasionally, presenting their work in galleries and museums also includes developing land acknowledgements that are accompanied by action, a true challenge for most institutions. In an exhibition this year at the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit, the group called on the board of the museum to commit to a land acknowledgement that incorporated actionable support for the museum’s Indigenous community. Around the same time, they decided to postpone their exhibition as a gesture of solidarity with the MOCAD Resistance. This is group of staff members who organized to demand institutional change and to voice racist and toxic work experiences with the museum’s director at the time, Elysia Borowy-Reeder, who was investigated and then fired. By being confronted with the challenges and conversations instigated by NRO, alongside the existing systemic issues the museum was grappling with, the museum eventually took steps to develop a land acknowledgement process. They also moved to fund the formation and work of the Waawiiyaataanong Arts Council, a coalition currently focused on transforming hollow institutional land acknowledgments into active and significant support. In instances like these, the situational quality of NRO’s work comes into play. They do not stop at a linear understanding of their work, or even a passive encounter. Whether one shows their work in a museum, watches it online, or joins their membership, NRO’s kaleidoscopic practice allows for engagements both micro and macro in scale. With a work like Never Settle: The Program, a forthcoming featurette that at first glance appears to be an advertisement for a slick decolonization self-help program, a persistent feeling of unease creeps through the testimonials and stock image-style scenes. Appropriating the tone and spectacle of infomercials, the video produces a familiar feeling that masterfully teeters between laughing from the satire (wait, is it even satire?) and laughing at oneself (wait, could that be me?). We see self-identified settlers reflecting on their own processes of coming to terms with their colonial worldview, couched between inspirational pseudo-institutional mantras like: “Start Really Living. Experience Clarity. Act With Confidence. Attract Abundance. Be a Part of the Solution. Leave Behind a Better World. Never Settle.” The video subverts the visuality of mass appeal to prompt what it means for each and every person watching to live in this settler-colonial reality. The answer for never settling may seem simple (don’t do it), yet within this answer lies the complexity. To “Never Settle” means to engage beyond one single strategy or one single state of mind, into a constant state of criticality. Image caption: New Red Order, Culture Capture: Crimes Against Reality, two channel video (still), 2020. Image alt text: In the center foreground there’s a form that resembles a monument to a soldier made from raw meat. The background shows a colonial style building in blurred focus and muted colors.]]>

Poetics of radical criticality in the work of Demian DinéYazhi’

December 30, 2020

by Anna Harsanyi

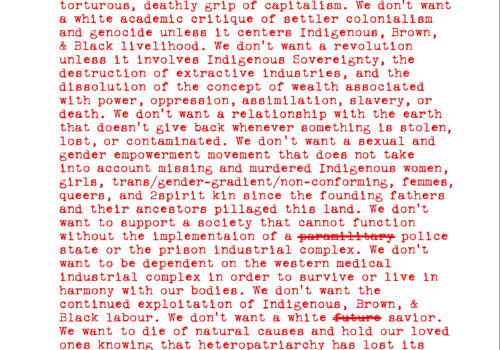

This is an examination of the work of Demian DinéYazhi’ by curator, arts manager and educator Anna Harsanyi. In the work of Demian DinéYazhi’, language and performance are creative tactics for puncturing the United States’ long history of erasure and destruction of Indigenous communities. Using the performative and confrontational power of text, DinéYazhi’ engages with the continued resistance work of marginalized communities. The artist’s provocations form moments to call today’s socio-politics back into their contexts of settler-colonial systemic violence. America in 2020 was consumed with many layers of devastation and chaos, including the Presidential election. Social media echoed the frustrations of many over a ballot of, yet again, cis white men. Circulating amongst social networks in the months before the election was Zoe Leonard’s 1992 poem I want a president, which begins: “I want a dyke for president. I want a person with aids for president and I want a fag for vice president and I want someone with no health insurance and I want someone who grew up in a place where the earth is so saturated with toxic waste that they didn’t have a choice about getting leukemia.” Leonard’s poem goes on to name those harmed by mechanisms of political inequality, demanding a President who represents her LGBTQIA+ community, and who has experienced struggle, and whose body has faced injustice. Though Leonard’s poem appeals to inclusivity and “we see you” empowerment, the feminist and queer artistic movements she was a part of also excluded Indigenous, Black, Brown, womxn of color, and non-binary individuals. Her statement, often looked to as an iconoclastic work of contemporary art activism, is furtively checked for its omissions by DinéYazhi’, who extends an alternative, more urgent, set of demands in We don’t want a president. (2018). These begin with:

“We don’t want a president. We don’t want tribal presidents. We don’t want a vice president or a congress or supreme court that does not seek consent or guidance from over 562 Indigenous tribes in this colonized country. We don’t want a nation state or a man-made border that severs ancestral traditions of trade and migration, or imposes on the sustainability of flora and fauna.”

The text continues towards a detailed and powerful reframing of what it in fact means to desire revolution or representation within the format of American government: the Executive Office and all of its administrative bodies are ultimately tools that perpetuate illegitimate occupations of Indigenous land and culture, and continued violence against its people. There can be no perceived “change,” “freedom,” “justice,” or any other shift when these outcomes are linked to the United States’ institutional practices. Through these assertions, DinéYazhi’ breaks open the common framings of public discourse, even amidst the purported progressivism of so-called “radical” social and cultural frameworks. In another instance, a recent performance titled SHATTER///, a collaboration with artist and composer Kevin Holden, was live-streamed at Portland Institute for Contemporary Art in September 2020. In a dimly lit room cloaked in a red glow, the artist recounts personal experiences as well as histories of Indigenous oppression. Holden’s guitar and pedals emit raw intensity, that at times envelop the vocals in cacophony. At a moment of crescendo in both the oration and the musical score, a destruction occurs. Behind the performers is a collection of objects that represent racist Indigenous stereotypes – a VHS of Disney’s animated film Pocahontas, a porcelain “Indian” tchotchke, and more; these were gathered in preparation for the performance at local thrift stores and antique stores/malls in the area. Thrown to the ground, stomped on, broken apart, their shattering is at once physical and metaphorical. This is an act of confrontation of the oppressive systems that created such racist objects, alongside the communities who consume and distribute both their material objecthood and the harmful meanings they encapsulate. Their obliteration, realized parallel to a wall of piercing sound, is a symbolic rupturing of the very social and political fabric that upholds these value systems, and their justification as harmless relics of “another time.” Though SHATTER/// has been performed in several venues in previous years, witnessing such breakage is especially cathartic and fiery in the present day. As conversations unfold about the future of the United States’ racist monuments and cultural heritage, and the history of atrocities they represent, smashing the material culture of this history and diminishing it to residue signals a reclamation of power necessary for confronting all efforts towards decolonization. Part of what makes the work of DinéYazhi’ so poignant is its intentional development outside of the boundaries set up by institutional structures. Their work does not “need” an institution or an exhibition in order to take place, in order to thrive and take powerful hold over an audience. Viewership is a relationship that the artist cultivates through a deep engagement with their practice as part of existing legacies of collective resistance. The magnitude of DinéYazhi’’s work becomes apparent through a delicate employment of the poetics of radical criticality. The work is often described by the artist as a gesture or an offering, an affective creative process rooted in deep intention and critical purpose. Such careful consideration allows for an experience of work that entwines form and context. Another one of DinéYazhi’’s projects, AN INFECTED SUNSET, serves as one such offering to the resistance work of marginalized communities, work that has been ongoing for centuries. A self-published long form text which is sometimes accompanied by a performative reading, it was conceived of in 2016, when large-scale violent injustices occurred in quick succession: the PULSE shooting in Orlando; the uprising at Standing Rock; the police suppressions of Black Lives Matter protests; the contentious election of Donald Trump. Though the artist could not join these movements in person, AN INFECTED SUNSET, which they wrote between 2016-2018, served as a means to contribute their energy towards these actions. It was delayed and shifted in style and content due to Trump’s election. The text is personal and reflective, critical and observational. It speaks of interior and exterior, but also historical and contemporary, lived experiences. The second half of the book, LIBERATED POEM, is unbound and the pages are not numbered–free from book form. When performing a reading, the artist leaves the pages to fall to the ground as they read from it, to be taken away by audience members or linger where they fall. But these words and messages are not discarded. They remain, as the artist recently stated, “a ceremonial offering to community…I think of poetry and performance and writing as gestures of that continued role and dedication that the artist has to communities. I may not always be able to show up or be there physically, but my work will…create space, opportunities and awareness about these atrocities that are happening and that we are actively resisting.” Image caption: Demian DinéYazhi’ and Radical Indigenous Survivance & Empowerment (R.I.S.E), We don’t want a president., 2018. Image alt text: Red typewritten text on a white background that reads: “We don’t want a president. We don’t want tribal presidents. We don’t want a vice president or a congress or supreme court that does not seek consent or guidance from over 562 Indigenous tribes in this colonized country. We don’t want a nation state or a man-made border that severs ancestral traditions of trade and migration, or imposes on the sustainability of flora and fauna. We don’t want corporations or an economic value system based on European dominion. We don’t want to be consumed, commodified, or held prisoner under the tortuous, deathly grip of capitalism. We don’t want a white academic critique of settler colonialism and genocide unless it centers Indigenous, Brown, & Black livelihood. We don’t want a revolution unless it involves Indigenous Sovereignty, the destruction of extractive industries, and the dissolution of the concept of wealth associated with power, oppression, assimilation, slavery, or death. We don’t want a relationship with the earth that doesn’t give back whenever something is stolen, lost, or contaminated. We don’t want a sexual and gender empowerment movement that does not take into account missing and murdered Indigenous women, girls, trans/gender-gradient/non-conforming, femmes, queers, and 2spirit kin since the founding father and their ancestors pillaged this land. We don’t want to support a society that cannot function without the implementation of a paramilitary police state or the prison industrial complex. We don’t want to be dependent on the western medical industrial complex in order to survive or live in harmony with our bodies. We don’t want a white future savior. We want to die of natural causes and hold our loved ones knowing that heteropatriarchy has lost its own war against itself. We want to create on our own terms, in bodies of our own choosing. We want to restore our relationship with the cosmos/earth and move beyond the concept of western “truth”. We want to be fearless. We want decolonization. We want to exist never having to comprehend the need to defend ourselves. To worship only the earth. Part of the exhibition A NATION IS A MASSACRE. Demian DinéYazhi’ R.I.S.E. : Radical Indigenous Survivance & Empowerment.” ]]>